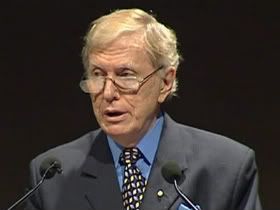

Michael Kirby

Michael Kirby is the Puisne Justice of the High Court of Australia. On 28 July 2010, he delivered this speech at the Singapore Bioethics Conference where he touched on human rights and HIV.

The Honourable Michael Kirby, AC, CMG

How did I get here? Well, of course, I travelled in the seductive comfort of Singapore Airlines which brought me safely from my office in Sydney. Yes, but what lay behind the trip? An invitation from my old friend Professor Alastair Campbell, Director of the Centre for Biomedical Ethics and the provision of an air ticket.

But dig deeper? Why did you come? Because I am fascinated with the impact of internationalism on my own discipline, the law . Law, in my youth, was unlike medicine, engineering, science and architecture. It was ever so local and, let’s be frank, rather parochial or imperial. That feature was imposed by the constant need to find local jurisdiction.

The awakening of law

Now, law is awakening to the relevance and impact of ideas that are global, species-wide, concerned with the biosphere and even with the larger universe. All of this has happened in little more than 60 years since the Charter created the United Nations out of the ashes and tears of war and from the suffering that destroyed mighty empires and required the world to start again.

Yes. We know all that. But what possible right do you have to be here? Why do you have the presumption to think that bioethicists (who are philosophers, physicians, nurses, theologians, social scientists, policy analysts and other practitioners in a multi-disciplinary field ), will have the slightest interest in what you have to say? What, pray, is your value-added that justifies your space in the programme?

Well, as a judge, I decided many controversial cases: whether damages should be awarded for wrongful (unexpected) birth ? And for so-called “wrongful life” ? These and many other decisions demanded a judicial resolution of what were truly bioethical questions.

Not enough, I hear you say. Who cares what a court, even a final national court, in Australia decides on such matters? This is the World Congress of Bioethics, my friend. We just do not have the time to look at the variable judicial decisions of courts in every country under the sun. No. You need much more than that to grab our attention.

What of my work in the Australian Law Reform Commission, so many years ago, that first introduced me to the issues of bioethics? What of the report we wrote so carefully on the dilemmas of the law on human tissue transplants ? Those proposals were adopted as law throughout Australia. They dealt with the definition of ‘death’. With consent. With opting out or opting in. Payment for body parts, and so on. Well, that is getting closer. But it is still hardly global.

AIDS/HIV and Human Rights

But then there is my work on the inaugural Global Commission on AIDS of the World Health Organisation (WHO), which proclaimed the AIDS paradox and the need to protect the vulnerable so as to change their behaviour and safeguard the majority?

Now, that’s better, I hear you say. HIV/AIDS is truly a world problem. And there was also the later work on the UNAIDS Reference Group on HIV and Human Rights. And last month, I was appointed to the new Global Commission on HIV and the Law, established by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This will tackle the way the law can actually support the struggle against HIV.

And also how the law can sometimes prove an obstacle to effective responses to the pandemic: the intellectual property laws that greatly enlarge the costs of anti-retrovirals. Or the laws on women that render them specifically vulnerable and disempowered. Or the laws on the vulnerable groups at greatest risk of HIV: injecting drug users; sex workers; men who have sex with men.

This is all very well, comes your response. But it is still rather particular. Remind yourself that this is a general world congress on bioethics. If you want to talk about AIDS, you should have taken your paper to Vienna last week and delivered it there.

A bold venture, a huge responsibility

In desperation, I invoke the decade I served as a member of the International Bioethics Committee (IBC) of UNESCO, between 1996 and 2005. During that time, I took part in the tail-end of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of the Human Genome and Human Rights and the International Declaration on Human Genetic Data . And then the clincher. I was part of the IBC when it accepted the challenge of UNESCO Director-General, Koichiro Matsura and developed the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (“the Bioethics Declaration”).

Surely it is useful to a World Congress on Bioethics to know something about the origins of that bold venture. To be aware of its objectives, course and achievements. And to be aware of some of the praise and criticism that has been voiced about it. I have more than the average reason to know about these things. The IBC elected me the chair of the drafting group that prepared the first text of the Bioethics Declaration, before it was sent off by the IBC to the Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (IGBC) in preparation for its eventual submission to (and endorsement by) the General Conference of UNESCO.

Alright, we give in. It looks as if we have to listen to you. But please make your remarks relevant to the big themes of justice in our world. Tell us exactly how this Bioethics Declaration can have the slightest value to the world’s struggle to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted by the leaders of 189 member countries in the United Nations. How will the Bioethics Declaration be any more than another paper document, like so many other paper documents that lie gathering dust in United Nations offices in New York, Geneva or Paris?

How did all that all that effort of the IBC make one iota of difference to the attainment of the common ideals of ‘justice’ in our world:

- To eradicate extreme poverty and hunger;

- To achieve universal primary education;

- To promote gender equality and to empower women;

- To reduce child mortality;

- To improve maternal health;

- To combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases;

- To ensure environmental sustainability;

- To develop a global partnership for development?

And above all, remember that we are meeting in Singapore. Please do not just give us a purely Western take on these issues. That is a risk of high level meetings held in Western capitals. But not here. Is it even really possible to talk about universal declarations? Are there any truly universal values that can be invoked to achieve the MDGs? Is this not another chimera by which Western ethicists try to stamp their values on the poorer, post-colonial nations of Asia, Africa and Latin America?

Did not a famous Singaporean leader once assert the uniqueness of ‘Asian values’? If there are such regional values, is it not a pipe-dream to propound universal or global values? Is the very idea of a World Bioethics Congress a kind of oxymoron? Are we all wasting our time at this Congress? Should we not just pack up, listen no more and go out to do the shopping?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

In the law, as well as in moral philosophy, context is critical. We cannot understand the Bioethics Declaration without appreciating where it exists in the emerging new international legal order. That order, in turn, grew out of the Second World War; the discovery of the mass genocide and the suffering that followed it; a reflection on the devastating weapons of mass destruction that accompanied and ultimately finished it; and an appreciation of the technology that spread this information to every corner of the world.

Long before the attempt was made in 1945 in the United Nations Charter (and in 1948 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ) to design a new world order for the safety of humanity, the more equitable sharing of its wealth and the defence of fundamental rights, efforts had been made in particular countries to express universal values that attach to being a member of the community.

In the Western world, these attempts included the Magna Carta of England in 1215; the Bill of Rights of Great Britain of 1689; the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. All of these instruments were greatly influential in the subsequent spread of the idea that human beings possess certain basic rights.

Even a powerful state or ruler could not take such rights away from them. The post-war images of the Nazi and other death camps were a powerful stimulus to the notion that, inhering in human beings, was a basic dignity that they could not be robbed of, even by apparently lawful means of the nation state.

Initially, it had been hoped that the United Nations Charter would itself contain a statement of fundamental rights. However, this proved impossible to draft in the time available . One of the obstacles was the insistence of the representative of [Nationalist] China that the drafters of any such instrument should spend at least a couple of years in Asia learning about Asian perspectives of such things. In the end, this was not done.

The Economic and Social Council of the United Nations established a Commission on Human Rights. It was mandated to present “a recommendation and report regarding … an international bill of rights” . The chair of that Commission was Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of the wartime leader of the United States. The principal drafter of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was John P. Humphrey, a Canadian legal scholar.

In the end, the UDHR was adopted by the General Assembly in December 1948 with no negative votes. There were, however, six abstentions. These were from the members of the Soviet Bloc, the Union of South Africa and Saudi Arabia. One reason for the high degree of consensus in the General Assembly was the generality and textual simplicity of the language of the UDHR.

To this day, it remains a most powerful and influential document, expressing not just civil and political rights but also economic, social and cultural rights . The latter reflected the insistence of the socialist countries and of the still small collection of member states from the developing world for whom the right to work ; to have access to education ; and to enjoy basic health care were quite as important as the right of a fair trial, to free elections and protection from arbitrary state power.

The UDHR, and the important international treaties that have grown out of its concepts, were influential in promoting the idea of binding legal obligations on the part of member states of the United Nations to respect the universal rights of their citizens and, indeed, of people everywhere. It is important to emphasise that the UDHR represented a stream of legal authority, largely drafted by lawyers. In that sense, it was a stream different from bioethics.

Up to recent times, that field of discourse has grown around the practical experience and values of members of the health care professions, expressed by their practitioners and by philosophers and moralists. Bioethics was viewed by its practitioners as much more ancient in its organised principles than the relatively recent invention of international human rights law. Yet, so far as any organ of the United Nations was concerned, it was that law, rather than pre-existing moral principles (including bioethics), that was binding on the United Nations and its agencies.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) became involved in bioethics some time after the primary international instruments of human rights had already been adopted. UNESCO was not the only agency of the United Nations at first to claim this responsibility. There were a number of tensions between the UNESCO initiative of the IBC and the interests of the WHO to protect what it saw as its own, largely medical, patch . That tension was to evidence itself in the work of the IBC and, specifically, of its working group preparing the Bioethics Declaration.

The first initiative towards such a Declaration arose in October 2001. It occurred, in part, because of an expressed interest by the then President of the French Republic, M. Jacques Chirac. A desperately short deadline of two years was offered to the IBC to prepare a new universal instrument on bioethics. The IBC reported that this timetable could be achieved . So, the drafting group was established. Contrary to some of the past practices of the United Nations, the group resolved to act in a transparent way.

The successive drafts of the Bioethics Declaration were published on the UNESCO website. Comments, criticism and input were invited, and received, from experts and laymen worldwide. Governmental representatives attended, as observers. They followed the work of the drafting group that took place between April 2004 and January 2005. So did representatives of the interested agencies of the United Nations.

Successive drafts were taken by UNESCO to regional meetings for consultations. In August 2004, a major public symposium was convened in Paris to which representatives of civil society organisations, religious bodies, scientists and other experts were invited. The final draft of the Bioethics Declaration was adopted by the plenary IBC. It was, however, thereafter amended in important respects by the IGBC.

As so amended, it was recommended by the Director-General to the General Conference of UNESCO, the agency’s governing body. On 19 October 2005, that body unanimously (and without any contrary votes or recorded abstentions) adopted the Bioethics Declaration by acclamation . Was the history of the UDHR to be repeated?

The Bioethics Declaration

The Bioethics Declaration set out to address “ethical issues relating to medicine, life sciences and associated technologies as applied to human beings, taking into account their social, legal and environmental dimensions” . It sought to provide a “universal framework of principles and procedures to guide States in the formulation of their legislation, policies or other instruments in the field of bioethics” .

The central provisions of the Bioethics Declaration comprise 15 basic rules, called “Principles”, propounded to define the obligations and responsibilities of the relevant actors in the field of bioethics. The arrangement of the Principles reflects a gradual widening of the objects being addressed. The initial Principles relate to individual human rights (human dignity; benefit and harm; and autonomy and individual responsibility). They then move to consider other relevant human rights (consent; privacy; equality; and non-discrimination).

Broadening their focus still further, there is a Principle requiring respect for cultural diversity and pluralism and for humanity as a whole (solidarity; social responsibility; and the sharing of benefits). Finally, broadest of all, Principles are stated which address our ethical obligations to all living beings and their environment (protection of future generations ; and protection of the environment, the biosphere and biodiversity ).

The most innovative features of the Bioethics Declaration include:

- The broadening of the focus of bioethics from the concerns of the human individual to the human community, to humanity generally and to the total environment;

- The attempted synthesis of topics traditional to “medical” bioethics and concepts obviously derived from the now familiar language of international human rights law;

- The introduction of important new ideas into bioethics, most especially those concerned with notions of universal access to health care and notions of social responsibility, not just individual entitlements, in the framing of bioethical principles.

Probably the most innovative provision of the Bioethics Declaration was the proclamation in article 14 of the Principle of Social Responsibility and Health. Relevantly, this Principle states:

14 (a) The promotion of health and social development for their people is a critical purpose of government that all sectors of society share.

(b) Taking into account that the enjoyment of the highest obtainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition, progress in science and technology should advance:

i. Access to quality health care and essential medicines, including especially for the health of women and children …;

ii. Access to adequate nutrition and water;

iii. Improvement of living conditions and the environment;

iv. Elimination of the marginalisation and exclusion of persons on the basis of any grounds; and

v. Reduction of poverty and illiteracy.

Returning to the question of what possible influence the propounded Principles might have to address the problems enumerated in the MDGs, it can be seen that the Bioethics Declaration shifts the ground of international public discourse on bioethics from a largely medical outlook to one that engages the individual, society and community, members of the human family, and all living beings and the biosphere. Thus, the lens of bioethics has been opened by the Bioethics Declaration.

The affirmative principle of health and social development is pronounced to be a duty. And virtually all of the eight MDGs are reflected in some way in the language of the Bioethics Declaration including poverty; hunger (lack of adequate nutrition and water); illiteracy; the health of women and children; the elimination of marginalisation that is so significant in combating HIV/AIDS; and attention to environmental sustainability that is such a feature of global thinking in the past decade.

If the question is asked, does the Bioethics Declaration, of itself, alter the world so as to assure that we attain the MDGs, the answer must be given candidly that it does not. But neither did the UDHR, of itself, ensure universal respect for human rights. Still, its provisions have been greatly influential in the independence constitutions of virtually every post-colonial nation in the world. The principles of the UDHR have spread widely to influence of international and local law and policy.

The machinery of the United Nations, however imperfect, now provides means to submit every country in the world to global scrutiny of its human rights record and to do so on a regular, rotational basis. Special representatives of the Secretary-General and special rapporteurs of the Human Rights Council have provided leadership to the global community on difficult and sensitive ethical questions.

I pay a particular tribute here to the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health (Mr. Anand Grover of India) for his valiant presentation, and defence, of his recent report before the United Nations Human Rights Council. He had to fend off critics who could not see the links between oppressive laws against women and minorities, and the shame, isolation and violence suffered by identified groups that provide the breeding ground for HIV infection. Ordinarily, there are no armies to enforce the UDHR or the Bioethics Declaration.

But there are now strong defenders of human rights, and specifically of the right to health. In the field of HIV/AIDS, and for the repeal of the counter-productive laws on adult private sexual conduct that are now urgently needed, the advocates include the Secretary-General of the United Nations himself (Ban Ki-moon) ; the administrator of UNDP (Ms. Helen Clark) ; the High Commissioner for Human Rights (Ms. Navi Pillay) ; and the Executive Director of UNAIDS (Mr. Michel Sidibé) .

As was intended, the new Bioethics Declarations makes a clear contribution to this global trend. It lifts the eyes of bioethicists from the patient’s bedside and the hospital ward to a new insistence on the relevance to the bioethics discipline for society, the community, humanity, all living beings and the biosphere. This expansion of thinking is appropriate to the age of the internet and to the pressing global problems of HIV, malaria, nuclear proliferation and climate change, that present, with the challenge of the MDGs, the greatest bioethical issues of our time.

Responses to the Bioethics Declaration

The response to the Bioethics Declaration has been mixed. Yet it has certainly included expressions of appreciation. Thus, Professor Thomas Faunce of the Australian National University wrote :

The question of whether bioethics represents an independent, normative discourse from international human rights, enjoying its own unique more relationship-oriented non-rational and nuanced approach to norms, a distinctive history, institutional structures and continuing valuable functions has hardly been debated [until now], let alone resolved.

Professor Faunce has expressed the opinion that medical ethics (a traditional sub-set of bioethics) may eventually be subsumed under the discourse of international human rights law and hence that the Bioethics Declaration is a step on that inevitable path . Other scholars have tended to similar conclusions, including Professors George Annas and George Smith in the United States.

In support of this view, Professor Faunce has explained why the harmonisation of bioethics with the advancing juggernaut of international human rights law is both timely and inevitable:

One of the main disadvantages of bioethics … is that it is at risk of becoming an irrelevant normative discourse in the great social justice debates concerning access to essential medicines taking place in global fora such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In that context, it is international human rights that have made the strongest inroads … Without instruments such as the [Bioethics Declaration], and in particular its ‘Social Responsibility’ Principle, bioethics may be less able to metaphorically ‘get its foot in the door’ concerning many of the great public health debates associated with the process of corporate globalisation.

As against these words of praise, there have been critics. Not without certain justification, some critics have lamented the lack of brevity, simplicity and elegance of the kind to be found in the UDHR. In part, these defects may be blamed on the very severe timetable under which the IBC was required to work, being approximately half the time that it took to draft the UDHR. In part, some obfuscation must be laid at the door of the IGBC, and of the governmental representatives and so-called governmental ‘experts’ who played with the IBC text, after it had been concluded.

This was their perfect right. Thus, the intergovernmental representatives insisted on the inclusion in the Bioethics Declaration of a completely new so-called “Principle” on the special case of “Persons without the capacity to consent” . The result was the introduction into the Declaration of a long, detailed and highly particular article of excessive specificity that was suitable for treatment (as the IBC itself originally proposed) either in a subordinate text or in editorial commentary.

As well, the IGBC imposed on the Declaration a notion of “free and informed consent”. This failed to accord with what the past president, Professor Ruth Macklin, has insisted is the proper direction of concepts of consent for contemporary bioethics. In the health care context, this is no longer a one-off agreement, signed by the subject as a formality. Today, it is an ongoing principle to govern the relationship between the health care provider and the recipient. These changes, like others that the IGBC has made in the past represent a typical instance of imposing political judgments on what was intended as a conceptual statement of broad ethical principles.

There have been other critics. Thus, Professor George Smith, not without justification, has been critical of the concept of “human dignity”. That notion is propounded in the Preamble to the Bioethics Declaration as a kind of Grundnorm and a foundation for its Principles. Professor Smith has noted that the concept of human dignity is somewhat problematic. He suggests that “[It] is open to abuse and misinterpretation” and that it “over-simplif[ies] a complex issue”. It can “encourage a form of paternalism, incompatible with the very spirit of self-determination” that lies at the heart of international human rights .

Professor Cheryl Macpherson has written in the Journal of Medical Ethics complaining that the Bioethics Declaration lacks ‘academic rigour and credibility in the bioethics community’. She expresses concern that there was insufficient evidence that its Principles were either universal or possible to implement. She complains that such Declarations need to be “responsive to the cultural and socio-economic realities of diverse stakeholders”, especially the poor and marginalised. She suggests that the drafters were unaware of the “complex interplay between culture, socio-economics, justice and human development”.

She accepts that the Bioethics Declaration did a service by establishing the primacy of universal human rights in a volatile field and by insisting that “the interests and welfare of the individual should have priority over the sole interests of science or society”. She also acknowledges the value of emphasising the protection of individuals and groups experiencing special vulnerability. However, she pronounces disappointment in the final product. Self-evidently, that product is but a step on the evolution of bioethics into a closer relationship with wider notions of human rights law and with other global concerns – including the justice concerns so prominently stated in the MDGs.

Although article 12 of the Bioethics Declaration makes it clear that cultural diversity and pluralism have to be given “due regard”, it still insists that these considerations cannot infringe upon, or limit, the universal considerations of “human dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms”. Nor can they alter the other Principles contained in the Bioethics Declaration.

Those who propose the inevitability of international and universal human principles, to apply to human beings everywhere because of their essential characteristics, need to respond to the criticisms of Professor Macpherson. And in those criticisms, she is by no means alone.

What of Asian Values?

What, for example, are we to make of the so-called “Asian values” or “African values” that are sometimes said to justify departures and exceptions from human endeavours to pronounce universal principles such as are found in the Bioethics Declaration?

Cultural and value differences between Asia and the West were asserted by several delegations at the Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, held in 1993. At that conference, for example, the Foreign Minister of Singapore warned that “universal recognition of the ideal of human rights can be harmful, if universalism is used to deny or mask the reality of diversity. At the same conference, the delegation of the Peoples Republic of China also emphasised regional differences. The speaker for the Chinese Foreign Ministry stated that “individuals must put state’s rights before their own”.

The former Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew repeatedly defended the notion of “Asian values”. He pointed to their suggested effectiveness in promoting economic success. He suggested that there is a “fundamental difference between Western concepts of society and government and East-Asian concepts”. He has explained: “When I say East-Asians, I mean Korea, Japan, China, Vietnam, as distinct from South East Asia, which is a mix between the Sinic and the Indian, though Indian culture also emphasises similar values”.

These are interesting ideas. But they are by no means universally accepted by intellectual leaders of the Asian region. Nor by the ordinary citizens, as I found when I served as Special Representative for the Secretary-General for Human Rights in Cambodia in the 1990s.

Writing in 1997 on the subject “Human Rights and Asian Values”, the later Nobel laureate Amartya Sen contested both the concept of regional exceptionalism to universal human rights and the notion that this was inherent in Confucian, and certainly Indian, ethical traditions. He said :

[T]he reading of Confucianism that is now standard among authoritarian champions of Asian values does less than justice to the variety within Confucius’s own teachings, to which Simon Leys, has recently drawn attention . Confucius did not recommend blind allegiance to the state. When Zilu asks him ‘How to serve a prince’, Confucius replies, ‘Tell him the truth even if it offends him’. … Confucius is not averse to practical caution and tact, but does not forego the recommendation to oppose a bad government. ‘When the [good] way prevails in the state, speak boldly and act boldly. When the state has lost the way, act boldly and speak softly’.

Far from being silent, Amartya Sen points to the endless arguing over ethical questions that takes place in India. And today, he could also point to the astonishing growth of the Indian economy which is occurring in the world’s largest stable democracy, that regularly changes its government peacefully and which boasts of courts of high integrity that uphold basic human rights, as the Delhi High Court recently did in striking down as unconstitutional the inherited Judeo-Christian colonial law against homosexual conduct .

In short, Amartya Sen acknowledges that the champions of ‘Asian values’ are often concerned with a need to resist Western hegemony. But he insists that human rights and political liberties are important in every country, including in the countries of Asia. And he concludes:

The so-called Asian values that are invoked to justify authoritarianism are not especially Asian in any significant sense. Nor is it easy to see how they could be made into an Asian cause against the West, by the mere force of rhetoric. The people whose rights are being disputed are Asians, and no matter what the West’s guilt may be (there are many skeletons in many cupboards across the world), the rights of Asians can scarcely be compromised on those grounds. The case for liberty and political rights turns ultimately on their basic importance and on their instrumental role. This case is as strong in Asia as it is elsewhere.

In essence, that was the reaction of the United Nations Vienna Conference on human rights of 1993 to the claims for regional exceptionalism. Universal human rights, that Congress insisted, are just that: universal, international, non-derogable, interchangeable. In our world, we do not always attain these ideals. Achieving them sometimes takes much time. But that does not prove, or even suggest, that they do not exist.

This is as true of my own country, Australia, as it is of any other. We have not always been respectful of the universal human rights of our indigenous peoples; of women; of Asian immigrants in the era of White Australia; of refugee applicants today; of the disabled; of people living with HIV and AIDS; of homosexuals; or of the poor and homeless.

But the discourse about these subjects (in the field of bioethics and everywhere else) has certainly changed in the past 60 years. It is no longer a discourse about local history, culture and tradition. If it were, South Africa would still be an apartheid state; Australia would have a legally supported whites-only immigration policy; the United States would still have segregation and anti-miscegenation; China would still exclude entry by all people living with HIV or AIDS and India would still oppress its homosexual citizens with outdated criminal laws.

Increasingly, and correctly, human rights is a universal discourse about human beings everywhere and their claim to equal rights. Nowhere is that claim more emphatic than in the assertion of the right to basic health care and in the general filed of bioethics.

Conclusion: Steps of a journey

So, for all its defects of content and drafting, the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights was an important step in the right direction. Bioethics can never again be divorced from the global concepts of human rights. That alone is a big step forward. It is also a step of reconciliation between the traditions of the health care professions and those of law.

Nothing less is acceptable in the organs of the United Nations. All of them, without exception, are bound by international human rights law. Nothing less is acceptable to the people of the world who today judge their governments and each other – sometimes quietly out of fear, often noisily out of assertion – against the criteria of universal human rights. Including, in the health care and bioethical setting.

So progress has been made, step by step. It is the duty of this Congress to take the mind of humanity further along the enlightening path of universal human rights.

Hi , thanks for covering

Would like to ask how did you get this speech? Is it an official version released by the conference or was it based on what was actually said?

Because there are some significant portions which I heard, but does not seem to be reflected here.

Thanks.

Dear Mathia,

Sources said that Judge Michael Kirby made an impromptu comment during his speech that he discovered he was gay at the age of 15. Is that the significant portion you were referring to?